Part One, Section B: Savvy Program Overview

What the Savvy Caregiver Program Seeks to Accomplish

Family caregivers occupy a critical place in the health care system for persons with Alzheimer’s and other dementing diseases. In fact, they are the center of the system — or, in most cases, the non-system. It is the care that they provide, in all its dimensions, that keeps the person in the community for as long as possible.

At the same time, they are often invisible in the larger system. Depending on the awareness and sensitivity of clinicians, they may or may not be present when the person with the disease is being examined or questioned. They may or may not be brought into the deliberations that result in care plans being formulated. They may or may not be given information about what is happening to the person or about how to provide care.

Not only do family caregivers go through their “unexpected career” with mixed amounts of help and support, the overall experience tends to be very harmful to their physical and emotional health. So family caregivers are in the paradoxical situation of providing great help — help that benefits society (by keeping costs down) as well as the person — and of paying a high price to do so.

The Savvy Caregiver program is a training program for caregivers. It is based on the notion that family members who become caregivers assume a role — caregiving — for which they are unprepared and untrained. The role is usually built on their relationship with the person for whom they care, but the role is different from the relationship. The role is a way of describing the work that they will undertake to care for the person, and that role can be understood in terms of the knowledge, skills and attitude that it takes to be able to do the work, to be successful at it, and to go through the experience with as much reward and as little distress as possible.

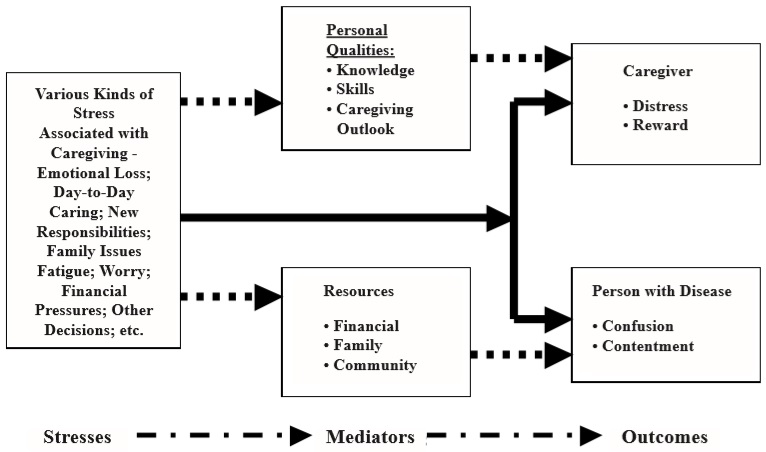

You are the leader of this training program. The program is modeled on programs that have been proven in field-tests to successfully increase caregiver confidence and reduce the adverse effects of caregiving. Savvy, itself, has undergone extensive field-testing and has likewise shown itself to improve caregiving confidence and reduce caregivers’ sense of distress. The program aims to help instill or increase a caregiver’s sense that they understand that caregiving is a new role that they have assumed and that they are effective in this role. The terms mastery, competence, self-efficacy, and confidence are all used, both in the Savvy program and in the larger field, to express this sense of self-appreciated effectiveness. The diagram on the next page outlines the theoretical basis of the Savvy program.

What is unique about Savvy is the angle it takes on caregiving and caregiver education. The many clinicians and educators who have contributed to the development of the program take the perspective that caregiving is a form of clinical work, and so caregivers need a form of clinical training. Throughout the program—and laced through the various program materials, like the Caregiver’s Manual—the central concept that is emphasized is the notion of strategy.

Over and over in the program, caregivers will be urged to learn, develop, and modify strategies that they will use to accomplish the goal of their caregiving—a goal that the program proposes, namely the “contented involvement” of the person with the disease in their daily life. In order to help caregivers develop such strategies, the program presents ideas that come from many disciplines and points them to information that comes from many sources.

We don’t claim these ideas or this information as our own; we provide citations and web addresses that both acknowledge the sources of these ideas and encourage the caregivers to explore further in the work and disciplines cited. What the program does is to offer distillations of these ideas and pursue a particular teaching technique (termed, by some, psychoeducation) that emphasizes active involvement in learning, independent practice of the ideas presented in group sessions, and very interactive debriefing and coaching that reflects on the practice and experiments that caregivers do at home with their persons.

The Theoretical Basis of the Savvy Caregiver Program

Family caregivers are under a tremendous amount of stress. Not only do they have to deal with the day-to-day reality of the situation — making sure the person gets safely and securely (and, hopefully, pleasantly) through the day—they are also dealing with their own feelings of sadness, loss, disappointment, etc. Caregivers typically take on added responsibilities both within the family (becoming the chief financial officer as well as the full-time laundry and housekeeping staff) and outside of it (they come to manage all the boundaries between the person and the various institutions with which they interact (physicians, nurses, bankers, social workers, lawyers, etc.). They are often faced with added financial pressures (having now to consider spending their own or their loved one’s assets on care-providing services). Very often they are also at the center of the cyclone of a family system trying to deal with a situation they don’t want and don’t understand.

Following the model diagrammed above, these stresses would — if nothing happened to dampen their impact — lead to a series of bad outcomes for both the caregiver and the person with the disease. If the situation were to proceed without anything to moderate it — the condition represented by the solid arrows in the diagram — the caregiver would surely be overwhelmed by the distress of the situation and the person with the dementia would struggle in a situation in which little or none of the confusion of the disease would be moderated by any effective caregiving. The person’s quality of life would suffer for this.

Notice that the diagram has a middle portion — the mediators. What the theory suggests is that as mediators are strengthened in a stress situation, the outcomes become more positive. This is the situation represented by the bold dashed arrows. In this situation, two kinds of mediators — the personal qualities of the caregiver and the number and amount of resources available to help the caregiver — can create more of a balance in the outcomes. In this case, the caregiver still experiences distress, but it is reduced, and they also experience — again, to a greater degree than in the unmediated situation — rewards for caregiving. Similarly, the outcome for the person with dementia is also improved. In the mediated situation, one in which there is more effective caregiving, the person with the disease is likely to have a higher quality of life, one in which they will feel greater comfort and less confusion.

The Savvy Caregiver Training Program

The Savvy program attempts to strengthen the mediators in the stress model presented above. The program’s principal focus is on strengthening mediators related to personal qualities. That is, the program focuses on helping caregivers to acquire and strengthen knowledge, skills, and attitudes that are appropriate for the role they have undertaken. How caregivers understand and interpret the situation they’re in, the kind of knowledge they have about what the disease is doing to their persons, the strategies they can bring to bear on the situation (strategies are skills and techniques that are informed by knowledge and improved through practice), and how competent or masterful they feel in the situation (how confident of their ability to manage the situation) — these all play big parts in determining how much the stress of the situation will result in negative or positive outcomes for caregivers and their family members.

The program places less emphasis on strengthening the Resource mediators. Sections of the training do focus on strategies for strengthening the family as a caregiving resource (and involving multiple family members in the Savvy training is recommended), and caregivers are directed to websites (such as those maintained by the Alzheimer’s Association and the Administration on Aging) where they might find help identifying community-based resources for caregiving. But the major program emphasis is on the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and attitude for caregiving.

Below are the areas of knowledge, skill, and outlook (attitude) that are taught or developed in the program:

Information and Knowledge

Many caregivers simply do not have the facts straight about what it is they are dealing with.

- They don’t understand — or believe — they are dealing with a disease that will not improve.

- They don’t have a very clear understanding about the course of the disease or it’s usually progressive impact on the person with the disease.

- They don’t realize, in any specific way, that Alzheimer’s and most other dementing diseases progress in stages and that the stage of the disease has great relevance for the strategies of caregiving.

- They usually don’t have any information on the impact of caregiving on caregivers.

Skills

Caregiving is a complex job and entails many tasks. It is a basic premise of the Savvy Caregiver program that few caregivers have received any training for the work they do as caregivers. Since the principal task of the caregiver is to manage day-to-day life with the person, these are the skills on which the program focuses. In particular, the program is designed to develop the following skills:

- How to take into account the person’s disease-produced losses in the manner in which they interact with the person.

- How to take the person’s disease stage into account in caregiving.

- How to help the person become and remain involved in daily tasks and activities that allow the person to be contented throughout the day.

The program also provides instruction in:

- Important self-care skills — especially those related to understanding and managing caregivers’ own feelings.

- Skills for making decisions as they continue their caregiving career.

- Skills for navigating family issues that come up while providing care.

Outlook or Attitude

The program aims to foster an increased sense of mastery in caregiving. There are at least three areas of attitude that the program tries to affect:

Objectivity. Caregivers have to learn to become less emotionally involved — at least when they are trying to figure out a caregiving problem — and more “clinically detached.”

- We want caregivers to become more analytic and experimental in their caregiving.

- We want them to be able to step back from the person and the situation and to examine — objectively and dispassionately — just what they are seeing.

- Then we want them to be able to put that observation together with other knowledge they gain from the program to be able to create a plan for what they want to have happen and how they will get it to happen.

Self Confidence. Caregivers have to believe they can do the work they have chosen to do. The program fosters growth in self-confidence through the home exercises and in-group coaching that constitute most of what happens in the latter part of the program. Caregivers learn new skills through trying them. They become more sure of their abilities through the successes they experience in trying them.

Self-Valuing. We want caregivers to appreciate their own work and worth.

- They should be clear about why they have undertaken this role (motives), be able to state the objectives they have in mind for it (what they hope to accomplish), and be able to say what it is they want to get out of it (rewards and satisfactions).

- They should also recognize the need for self-care — that they have an obligation to themselves and the people for whom they are providing care to preserve themselves.

What is the Savvy Caregiver Program About?

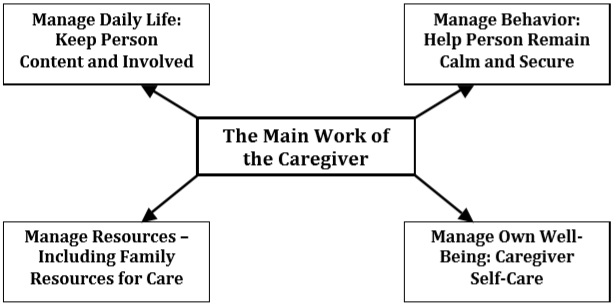

The diagram following portrays what the Savvy Caregiver program is about. At the center of the program is the assertion that caregiving is work, a task or role, and that (for almost all who fill the role) it is work for which most caregivers are unprepared and untrained. The Savvy Caregiver program provides training for the caregiving role.

The four boxes surrounding the central focus of the program represent the main content of the program. Each area of content is described briefly below.

Managing Daily Life

This area of content makes up the majority of the content of the program. The first four sessions of the program deal, in sequence, with the impact of Alzheimer’s and similar progressive dementias on the person with the disease.

The idea is to take caregivers through the ways in which these diseases affect thinking, feeling, behavior, and the ability to do things in life. Each of these four topics is presented in the same way and with the same objective in mind:

- First, the content of instruction — and this material is typically provided both in the form of a talk that you will give and in written information in the Caregiver’s Manual — concentrates on how the disease affects one of four areas. Basically, the instruction unpacks for the caregivers the ways in which these diseases gradually erode the person’s abilities to: (1.) use normal thinking powers, (2.) maintain emotional balance, (3.) direct their own actions, and (4.) do everyday things.

- Next, each of the losses presented is looked at from the perspective of the caregiver. The basic question that is addressed is: if the person loses this capacity, what should you expect? How should you prepare yourself for what you are likely to see happening?

- Finally, each section on losses ends with a focus on the development of caregiving strategies: if this is what’s happening to the person, and if this is what you can expect, what should you do to make this situation as positive as possible?

The idea is that caregivers are responsible for getting themselves and their persons through each day as successfully and effortlessly as possible. The program teaches that the caregiver is responsible for managing the day and that as the disease progresses, they become more responsible. In order to succeed in this task, the caregiver has to develop a caregiving repertoire — a set of strategies they can call on both to structure the day and to respond when things don’t go as planned (and to protect themselves from the possible emotional damage that can occur). In all of this, it is useful to have a general caregiving goal in mind, and the program suggests that an appropriate and feasible caregiving goal is to help the person become and remain content and involved in everyday tasks and activities.

The program teaches a number of techniques for enabling the caregiver to help their person become and remain contentedly involved in things throughout the day. In addition to clarifying the cognitive losses that occur with dementia and their implications for caregiving, the program teaches a staging system that helps caregivers understand how a dementing disease like Alzheimer’s affects the person’s ability to do things.

The system is one that combines a traditional Early-Middle-Late structure with an occupational therapy-based numerical staging system, the Allen Levels of Thinking. As part of the program, participants may arrive at a working estimate of their person’s disease stage. The program then links this estimate to strategies of Structure (the design of and environment for tasks and activities) and Support (methods for communicating with the person to help them begin and stay with a task) that help caregivers design tasks, activities and events appropriate to their person’s strengths and likely to help them become involved. The program encourages the development and/or strengthening of daily routines to promote comfort and familiarity.

Managing Behavior

Difficult behaviors by persons with dementia are strongly linked to caregiver distress and burden. The program attempts to give caregivers a basis for understanding behaviors they might consider difficult or troubling. Moreover, it provides strategies for quelling and/or responding to the behaviors—so that they reduce in intensity or stop or so that the caregiver finds them less troubling. The program encourages caregivers to develop strategies — stock or routine responses to frequently occurring situations that they find troubling — for example, developing one or two standard answers to their persons’ repetitive questions.

Managing Own Wellbeing

The feelings associated with caregiving can be overpowering and even incapacitating. The program examines the impact of caregiving on caregivers and provides tools for caregivers to examine their own feelings and to do something about them — especially those that are negative and reinforce the sense that they are powerless in the situation. The program also urges caregivers to examine their own interests and to have a repertoire of things that they will do when they can free time to do them.

The focus on having caregivers be conscious of managing their own wellbeing ties in with the program’s emphasis on this being a form of clinical training. Becoming aware of the impact of the work on one’s own self is a part of the training of every kind of clinician. We train nurses and physical therapists and doctors and social workers that the people and the conditions they’re dealing with can affect them, can get to them. We train them both to recognize that this can happen and we train them in what to do to avoid it and to deal with it if and when it does happen. If we acknowledge that caregivers are playing a similar clinical role, we have to help them deal with the emotional impact of the role, just as we do with other clinicians.

Managing Resources

Content about this topic is in two parts. The first centers on the family as a resource for caregiving. The program provides a description of family caregiving types and encourages caregivers to figure out in which kind they find themselves — and which kind they would like to have. The program provides a structure for strengthening family involvement in caregiving. The second area of content regards decision-making. Regardless of their previous role in the family, the caregiver is now thrust into a more prominent decision-making role. Whether it is deciding what to do with the day or whether and when to sell the family home, the caregiver has to make decisions. The program provides a technique for processing information and making decisions.

Mantras for the Program

There are three themes that recur throughout the program, three messages that you will find yourself repeating across all of the sessions in one form or other.

You’re in Control

Taking charge, giving directions, making decisions for another person — these are all actions that make us uncomfortable — perhaps even find repugnant — because of the profound sense of respect for personal autonomy that we hold as a fundamental cultural value. To be successful in the role, a caregiver has to take control of the situation and the person. This is a progressive process, one propelled by the progress of the disease in the person. But in order to meet the modest caregiving goal this program proposes (keeping the person content and involved) and in order to retain their own sense of wellbeing, the caregiver has to recognize that the disease at work forces them to cross this line and to be in control.

Don’t Just Do Something; Stand There: All Behavior Has Meaning

Every part of the content backbone of the Savvy Caregiver program — relating to the impact of Alzheimer’s and other progressive dementing diseases on the person’s thinking, feeling, behavior, and ability to do daily tasks and activities — has a core message: watch carefully and methodically before giving a name to a behavior or trying to do something about it. Watch the behavior and try to figure out what the person is trying to “say” by the behavior, because it does mean something.

Deciphering the behavior isn’t always easy, and the caregiver often as not won’t get at the meaning on the first try, but forming a response based on the best sense of what the person is expressing by whatever it is that they are doing gives the caregiver the best chance of restoring order to the world.

So What? (Curb Expectations)

Alzheimer’s and similar progressive dementias as well as more static dementias change everything. They change how people with the diseases look at and make sense of what’s in front of them. It changes their ability to do things in the world, including how long it takes them to do things and how well they do them. They will never again be as good at doing things as they once were. They will never again do things well that they used to excel at. Caregivers have to recognize this, and they have to accept the fact that, as these diseases progress, the pace of the day will slow and the quality of performance will diminish.

To avoid frustration — their own and the frustration they will transmit to (and therefore provoke in) their persons, caregivers have to let go of expectations based on who their persons used to be and what they used to be able to do. The caregiving goal — content and involved — only means that the person has times during the day when they are doing something that is keeping them occupied and that they are deriving some kind of enjoyment from doing that. The goal has nothing to do with speed, accuracy, or excellence of performance. Caregivers will be happier and more relaxed if they can let go of those expectations.